|

Neal Cassady is one of the more enigmatic "Beat" writers of the '50s, probably because he gave us only one book before he died at age 42 -- about the standard lifespan for a Beat. Sure, Cassady figured prominently in at least two others -- Jack Kerouac's On the Road and Visions of Cody -- and drove the bus for Ken Kesey's Electric Kool Aid Acid Test. But who was he, really?

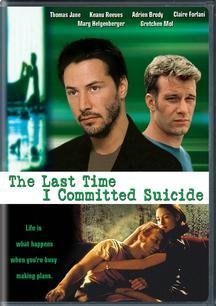

Well, if we're to believe Stephen Kay, writer-director of The Last Time I Committed Suicide, he was a pool-playing, car-stealing drifter of an ex-con who haunted Denver's back streets and dreamed of a better life while loving the one he had. Well, if we're to believe Stephen Kay, writer-director of The Last Time I Committed Suicide, he was a pool-playing, car-stealing drifter of an ex-con who haunted Denver's back streets and dreamed of a better life while loving the one he had.

A sort of one-man erotic SWAT team, he be-bopped from one amorous adventure to another with "Sweet Sweet Sugar Blues" blaring through his 20-year-old brain -- all the time dreaming of a little house on the edge of town with a white picket fence, a woody station wagon, a two-car garage and a happy toddler playing on the porch.

That makes for a hard life but good cinema, and Kay has done a superb job of capturing both an unusual time, 1946, and an unusual personality on film.

At its best, Suicide is 95 minutes of nonstop agitation, a closeup look at the libido of a former altar boy on the verge of helping create the country's first legitimate counterculture.

Right at home in that role is relative newcomer Thomas Jane, a muscular biped with the nervous energy needed to portray the man once described as the incarnation of American hipness. Jane is always on cue and in character, whether he's eulogizing grilled cheese sandwiches or holding a death-bed vigil outside the room of a woman who's attempted suicide on his bathroom floor. In a few years -- should he prove better at survival than the man he portrayed -- he'll be doing the James Dean story.

Much of the credit, of course, has to go to Kay, who's given Suicide the rhythm of a beat novel and the look of a beat poem. Images come and go, shifting from black & white to color, reverberating and churning up recurring themes.

The story line -- based on a real-life letter from Cassady to Kerouac -- crisscrosses itself and dips liberally into Cassady's random access memory for necessary details from his not-too-buried past. Cassady was a character who lived right on the edge, literally and legally, and Kay's film captures all the attitude, agita and angst of such a lifestyle.

If Suicide sounds challenging to watch, it can be, at least until two-thirds of the way into the film. That's when Kay manages a seamless downshift into a stable narrative -- gives up be-bop to ballad, you might say -- and begins the long windup to his final delivery. And what a punch it is: solemn, staggering and chock full of ironic insight.

Fifty years after the fact, 40 years after their time, Stephen Kay has at last delivered a film worthy of the Beats. We can only hope there's more where this came from.

[ by Miles O'Dometer ]

|

![]()

![]()