|

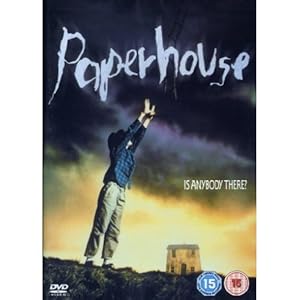

A child's hands open a school notebook. Her pencil moves across the page. Within a few minutes the page is home to a house. Within a few hours, the child is inside the house, and things will never be the same -- for either of them.

Between the last days of childhood and the onset of adolescence lies a vast shadowland of hopes, fears, dreams and hormones. Young Anna Madden (Charlotte Burke) has all these and more. Mostly Anna has glandular fever, which, when crossed with her already fertile imagination, leads her into a series of dreamlike adventures in her fictitious Paperhouse.

Those adventures revolve around two very different people: her father (Ben Cross), who has been working abroad for some time, and a young man named Marc (Elliott Spiers), whom she has never met. In real life, Marc, who has muscular dystrophy, is in a London hospital with a life-threatening chest infection. In Anna's dreams -- or whatever they are -- Marc lives in the paper house, where Anna visits him, comforts him, does her best to help him recover, and, ultimately, grieves for him. Those adventures revolve around two very different people: her father (Ben Cross), who has been working abroad for some time, and a young man named Marc (Elliott Spiers), whom she has never met. In real life, Marc, who has muscular dystrophy, is in a London hospital with a life-threatening chest infection. In Anna's dreams -- or whatever they are -- Marc lives in the paper house, where Anna visits him, comforts him, does her best to help him recover, and, ultimately, grieves for him.

Works of the imagination are always difficult. In Paperhouse, the difficulty is multiplied by a number of difficult characters, not the least of whom is Anna herself. Whether she's feigning illness to get out of school or feigning health to get out of bed, Anna is as troubled as she is trouble. Impossible to read, impossible to please, she's every parent's nightmare.

Fortunately, Burke is more than up to the part. Her pensive face and thoughtful eyes help us hang in there with Anna until the complex reasons for her complex behavior become apparent. But the real stars of Paperhouse are director Bernard Rose, production designer Gemma Jones, and composers Stanley Myers and Hans Zimmer. Rose and Jones (who also plays Anna's physician, Dr. Nichols), have given the film a look that's hard to forget. The real-world sequences in London and the west of England have a soft, textured look that contrasts markedly with the fever-driven images that grow out of Anna's drawings. The latter are decidedly hard and two dimensional, inspired in both light and line by the works of Picasso, Andrew Wyeth and Rene Magritte.

These reference points, most notably the last, help make the bridge between Anna's real life and dream world more substantial, and Anna's dream logic more believable. On top of that, Paperhouse offers a musical score by two masters, Myers and Zimmer. Myers, who first broke in with the Dr. Who television series, and Zimmer, who has scored everything from Moonlighting to Muppet Treasure Island, score once again, this time with thick layers of brooding chords that make even the most innocuous scenes seem ominous and dire. Juxtaposed on the colorful landscapes, or welling up under the dark skies that presage Anna's father's assault on the house, the music intensifies the vague sense of dread that Rose builds to the breaking point again and again as his film works its way toward a conclusion that's both predictable and surprising.

Paperhouse has its rough spots. There's Dr. Nichols' inexplicable willingness to discuss details of Marc's case with Anna, or moments when Anna's parents seem unusually thick, even for parents. But it's a film that starts strong and gets better as it goes, even if it has to pull itself back from the edge of a mawkish cliff or two along the way.

A Paperhouse it may be; a paper tiger it's not.

[ by Miles O'Dometer ] |

![]()

![]()