|

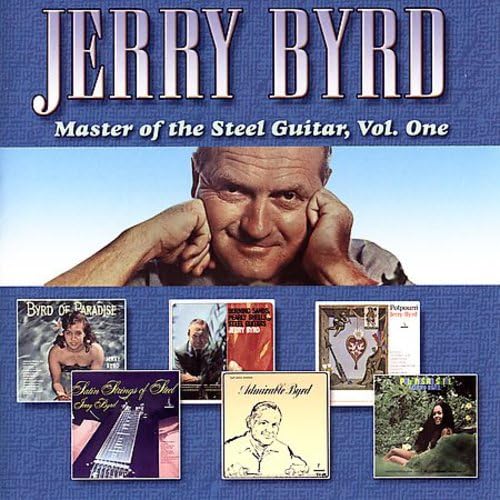

Jerry Byrd, Master of the Steel Guitar, Vol. 1 (Cord International/Hana Ola, 2005)

By 1972 he was tired of Nashville and eager to take his music back where it had come from, even if the steel guitar had passed out of style in Hawaii itself. From then until 2005, when he died, he lived, played and taught in Honolulu. He helped revive interest in steel guitar among younger native musicians, a few of whom repaid the favor later by complaining that Byrd's playing wasn't "Hawaiian" enough. Much of the material on this welcome retrospective, true, is not traditional Hawaiian music. Taken from various Monument sessions from 1961 through 1967, they showcase diverse influences, including Western swing, pop and lounge. Hawaiian sounds are defining, however, even in "Danny Boy," also in the Roy Orbison-penned "Memories of Maria," notwithstanding Fred Foster's unmistakable production imprint. "Bird of Paradise" (1961), with its oooing female chorus and cackling tropical birds, comes out of a strain of lush, faux-island music that drives morbidly sensitive, post-modernist types to fits of righteous rage -- cultural patronization fueled by Western imperialism is the specific complaint -- but such carryings-on seem wildly out of proportion. This is, after all, just escapist entertainment, and as such "Bird" is pure atmospheric fun, and no statement about anything whatever. Byrd's playing is all that the legends attest, and they attest that he was, as the usual accolade had it, "master of touch and tone." In lesser hands some of this could be pure schmaltz, but these are not lesser hands. Though Byrd's approach has nothing to do with anything remotely fashionable in this rougher and cruder age, this anthology touchingly communicates something more than 15 cuts of pretty pop music. It's more like a little vision that Byrd managed miraculously to turn into sound.

|

Rambles.NET music review by Jerome Clark 13 January 2007 Agree? Disagree? Send us your opinions!

|