| Bernard Cornwell: making histories Bernard Cornwell has authored nearly 40 novels plus short stories in two decades of writing. His stories cover everything from his signature Sharpe series, set in the Waterloo era, to Arthur's Camelot and modern-day thrillers on the high seas. He has seen the Sharpe series turned into a series of successful movies, and there are rumors of a film based on his Arthurian tales.

Bernard Cornwell: Not sure -- won't think about it till I write the book later this year -- but I'm pretty certain there are more than two books to come! Probably at least four more, but I'm determined to keep him moving forward, which means I won't, again, write any prequels. D.M. Sharpe's Escape takes Richard Sharpe to dead center of the Sharpe cycle: at the start of his romance with Teresa. How hard was it to go back, to write about characters whose fate had already been sealed in the other books? B.C. It's not hard -- but it means I can't introduce new characters who will stay through the series, simply because the series is already written! This is a nuisance, but I can live with it. What it does mean, sadly, is that any good character either has to die, or just fade away, but luckily the original series has plenty of people to use. It also means there are countless variations between things I said in the original series and what actually happens in the second series, and lots of readers are kind enough to point out these mistakes! D.M. The Sharpe books were turned into a series of small films starring Sean Bean (Boromir in The Lord of the Rings). Bean is a very talented actor and many applauded the films, giving them critical acclaim -- within their budget limitations. Writers "see" their characters in their minds and are often disappointed when a work comes to film. Were you pleased with Bean as Richard Sharpe? B.C. I was delighted! He didn't look like my Sharpe, but I didn't mind that, and I thought he played the part wonderfully. I don't see Sean Bean as I write, but I do hear his voice, and I think that's a great compliment to him.

B.C. Sean Bean, of course! D.M. In Sharpe's Enemy and Sharpe's Rifles, you created one of the nastiest bad guys in Obadiah Hakeswill. The marvelous actor Pete Postlethwaite brilliantly brought Obadiah to life on film. Little old ladies would run this guy down on site! Actors always say playing the heavy is such fun; was creating Hakeswill as much fun for a writer? B.C. It was wonderful fun, and the stupidest thing I ever did was to kill Obadiah. One of the nice things about writing the Indian adventures (Tiger, Triumph and Fortress) was the chance to bring him back. I always enjoyed myself writing him -- I'm VERY fond of Obadiah! D.M. The Sharpe films were small budget, so many of the battle scenes were a little "thin" compared to the rich scope of your works. Taking that into consideration, do you feel the movies did justice to your books overall? B.C. I think so -- and plainly, the audience enjoyed them, and they introduced many people to the books, which they also enjoyed, so I was entirely happy.

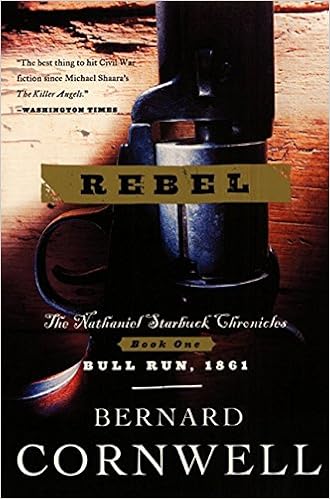

B.C. Mainly because I thought the Sharpe series was finished (this was before the TV series was made) and I was looking for another series that would be similar, and because, by then, I had moved to the U.S. and I had become interested in the Civil War. It seemed a natural fit. Sadly, for Starbuck, though, Sean Bean came along and I went back to Sharpe. D.M. Some reviewers noted your love of the South was clear in your writing in the Starbuck series. I have found the commanders of the South very interesting. Hard fighters, religious, colorful -- they just seem to fire the writer's imagination. What, in particularly, inspired you to focus on this period in American history? B.C. Because it's the most astonishing and most dramatic period of U.S. history, far more so than the Revolution, and because it's stuffed with good stories, great characters and lots of drama. I've noticed there are no great films, plays, etc., about the Revolution, but plenty about the Civil War -- the truth is that, once you examine the Revolution closely, you discover that a lot of it is myth, and so it's probably best left where it is -- in the realm of magnificent legend. D.M. Dealing in history and lore, I often run into people claiming only a person from that country can understand the complexities of their own military conflicts. Frankly, I do not agree, and think that often an outsider brings a fresh point of view. You are a Brit, writing about a very complex and difficult period of the American history. Do you think your fresh perspective aided in you seeing the causes and effects of the Civil War?

D.M. Again, you switched back to Britain and into another time period with your Warlord Trilogy -- Winter King, Enemy of God and Excalibur -- dealing with the Arthur legend. Taking your own path, you deviated from the traditional Grail lore, conjuring a more human, more complex Arthur, who often acts rashly and with tragic ramifications. Your Arthur is the regent for his nephew Mordred, grandson and true heir of Uther Pendragon. You say of all the works you've created these are your favourite. What makes them more special than the rest? B.C. I wish I knew! I suppose the answer is that I enjoyed writing them the most, and usually when you enjoy writing something it shows in the finished book. It was fascinating to deal with the characters, most of whom were already well known, and try to put them into a realistic post-Roman background, and cope with the conflict between paganism and Christianity, and try to suggest reasons why Arthur has become such a towering hero. Above all, though, they were simply fun to write. D.M. Will you go back to more stories of Arthur? B.C. No, that story is told. I wish I could go back, but there's no more to tell, so it's best left alone. D.M. With the huge success of Tolkien's Lord of the Rings movies, Hollywood is scurrying to find something with the same magnitude and sweep, and with many of the similar fantasy/myth elements. The Warlord Trilogy would fit this bill perfectly. Is there any chance they will make it to the screen? D.M. I appreciated your approach to your novel Stonehenge. So many visit it and cannot envision that mere people made the ring. They believe Merlin did it by magic; the druids are firmly -- and falsely -- fixed in everyone's minds as the creators, while some have even hinted aliens are responsible. Your tale was imaginative and frankly ambitious in scope, but more rooted in real history and lore of the period. You've been praised for the description in the technique in the construction of the temple. How did this novel challenge you? B.C. The biggest challenge was to construct a theology to fit the stones, and I'm not certain I really succeeded. I was also disappointed that the background was so dull -- that everyday life circa 2000 BC really did not provide much material -- I spent months researching it, but rarely got a flash of light. D.M. Of all your books, Stonehenge seems to have garnered mixed reviews. Do you think possibly it was more demanding to the reader -- not as familiar with ancient history and lore -- that it was harder for them to relate to, so they were not quite sure what to make of this work? B.C. Probably because it is not my best book! Too dutiful, too in thrall to the research, not enough story.

B.C. Mostly in the fact that he has the grail to pursue. He's educated like Starbuck, so is a more reflective soldier than Sharpe, but the real difference is in the stories rather than the character. D.M. You say the Grail Trilogy is finished, but that Thomas of Hookton will return in further adventures. Can you hint where his new adventures may take him? B.C. I'm not sure there will be more Thomas of Hookton stories -- I thought there would be, but I suspect his tale finishes with the grail, so at the moment I'm content to leave him alone -- at least for a year or two. D.M. Gallows Thief, another of your novels, is a detective story. You set the period as Regency London, a time when there were no detectives as such. Captain Rider Sandman was a veteran of Waterloo. Down on his luck, he moved into this "new" profession. Arguably, this could have been another tale for Richard Sharpe. Did it start out that way? Will there be more tales of Rider Sandman? B.C. There was no one called a "detective," but the British government did, from time to time, appoint an investigator to enquire into the circumstances behind a criminal conviction, and that investigator was a detective in all but name. He was probably the first detective, which meant he had no precedents or experience to help him. It could have been a tale for Sharpe, but he's a slightly blunt instrument and I thought the story needed someone with a little more delicacy -- and if I'd used Sharpe then everyone would have wanted the characters from the Sharpe books involved -- it was better to start something entirely new. And yes, I think there will be more of Rider Sandman. D.M. You became a writer in a roundabout way. You worked for the BBC for 10 years, but then married an American. Due to the family situation, you relocated instead of your wife. Strangely enough, you were denied a green card, which would have permitted you to work in the U.S. I can imagine that was very frustrating, and at the time, it seemed a rather bad stroke of luck. However, you took the lemon and made lemonade, so to speak. You began writing your first Sharpe novel. Do you look back and say what a blessing-in-disguise the denial of a work permit turned out to be?

D.M. You and your wife, Judy, co-wrote several books under the penname Susannah Kells: A Crowning Mercy, Fallen Angels and Coat of Arms. How does the creative process differ between writing on your own and working with a partner? Will you ever co-author more books with her? B.C. You argue more! So it's not worth it! D.M. With all the research you do in preparation for your books it seems a forgone conclusion that you read a lot. But do you read fiction for pleasure? If so, are there certain authors of whom you are a big fan? B.C. Ian Rankin, Dennis Lehane, John Sandford. D.M. You also touched on another period, back on the U.S. side again, with Redcoat, a tale of two men, Brit Sam Gilpin and Rebel Jonathon Becket. You used them to illustrate the divided loyalties of the period of the Revolutionary War. Given the time, with all these wonderful series you have to juggle, are there a period or periods in history still beckoning to you to tackle? B.C. There are! But as you say -- there are so many series to juggle that I try to forget the other periods, though I am just embarking on a new series about the making of England in the 9th century -- the time of Alfred the Great, his son and grandson. D.M. Aside from all the many historical novels you have penned, you also have five contemporary adventure/suspense novels Wild Track, Sea Lord (re-titled for U.S. release as The Killer's Wake) Crackdown, Storm Track and Scoundrel. Each has a different lead character and the only thing really tying them together is the fact they have the sea back the setting. Since you seem to write in series or trilogies, what made you do just stand-alone titles with the contemporary books? B.C. Never thought about it. Just seemed the right thing to do at the time! D.M. Ever consider taken the great-great-great grandson of Richard Sharpe and doing a modern series? B.C. Never thought about it -- and probably won't. D.M. Finally, I would ask about advice, which I am sure you are grilled continually -- so I apologise if the questions seems redundant to you. However, I know how hard it is for new writers to see their novels published, and most especially this is true for historical fiction. It is one of the hardest genres to break into. What advice do you have for writers of historical fiction hoping to see their novels make it into print? B.C. The first hurdle of any new writer (other than writing the book, of course) is getting a manuscript onto a real person's desk instead of onto the slush pile (the slush pile is the vast heap of unsolicited manuscripts which turn up at all publishers' offices and which rarely get read), and my advice has always been to find an agent. How do you find an agent? Go to your local library and consult The Writer's & Artist's Yearbook (or its U.S. equivalent). Or subscribe to Publisher's Weekly or The Bookseller and read the trade columns -- or write to an author you like and ask for a recommendation. Your book must have an original voice. And once you have your story, you must keep it moving. Why not learn from successful authors? Disassemble their books, then set out to do better. If you worry that the long scene in your chapter four is much too long, then see how other writers tackled similar scenes in a comparable stage of their book. The answers to a lot of first novelists' questions are already on their bookshelves, but you have to dig them out. A page a day and you've written a book in a year!

|

Rambles.NET interview by DeborahAnne MacGillivray 3 April 2004 Agree? Disagree? Send us your opinions!

|