|

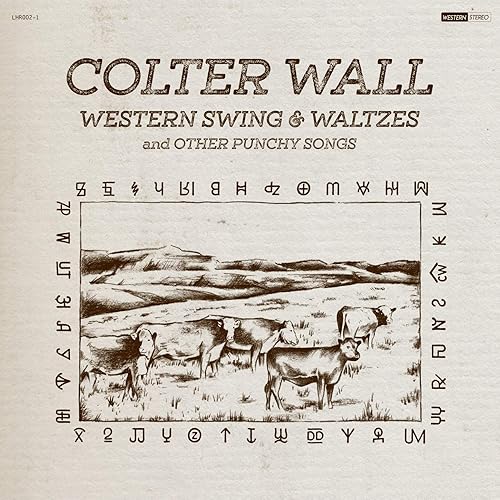

Colter Wall, Western Swing & Waltzes & Other Punchy Songs (La Honda/Thirty Tigers, 2020) Sometime ago Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart allowed as how, if unable to define hard-core pornography, "I recognize it when I see it." The same could be said of authenticity. It defies definition, but you recognize it when you see it. At least that's what I think whenever I hear Colter Wall, who could be about three times his age and a refugee, rode hard and put up wet, from a century or more ago.

In the real world Wall, born in Swift Current, Saskatchewan, is all of 25 years old. He discovered country and folk music exactly as I and countless others did: by listening to records, finding what one excites one, and following one thing to another till one day you know who Ramblin' Jack Elliott is. And a whole lot of other interesting artists you didn't hear on the radio or from your small-town friends. If you have a musical gift, as Wall does and I don't, you start playing the stuff yourself and maybe writing your own songs. If your genes are right and your soul is old, you can sing "I Ride an Old Paint" as if you were there at its creation, or maybe its creator. In point of fact, Wall sings "Paint" on Western Swing & Waltzes & Other Punchy Songs. He does a thrilling interpretation of what remains among my all-time favorite songs; I first heard it as a kid, which is not recently. He also makes Marty Robbins's gunfighter ballad "Big Iron" seem grounded deeper than the Hollywood West, in which it has a stronger claim than in tradition. The great Norman Blake once wrote a dark answer to it, the unforgettable "Billy Gray," sung from the perspective of the doomed outlaw and of all that followed his death. I hope Wall will record that, too. He also renders an outstanding interpretation of "Diamond Joe," which I first encountered on a Ramblin' Jack album and I suspect Wall did, also. This is the cowboy "Diamond Joe," not the traditional song of the same title about a riverboat. The cowboy "Joe" has an old melody, from the 19th-century "State of Arkansas" aka "John Johanna," with delightfully crafted lyrics by the late Lee Hays who drolly relates the tale of a cowhand's travails with a greedy range boss. I don't know how young Wall does it, but he handles the song so well that maybe it'll sound as new to you as it did to me. The self-produced Western Swing has an aural resonance that suggests it was recorded in a barn, which is to say some airy space, or maybe a haunted house where the notes pass into an otherworldly ether as opposed to ordinary air. Wall's distinctive voice seems born (or borne) on horseback. A handful of other instruments sometimes accompany his acoustic guitar as he sings his songs (originals and covers) not so much of an especially romantic West as of a place where circumstances have dropped you and you make do amid whatever pleasures and misfortunes fall your way. On the other hand, "Rocky Mountain Rangers" could pass for an oldtime ballad circa 1885. Writing an imitation traditional song is a lot more difficult than you'd think, but this one lands within shouting distance of Tom Campbell/Steve Gillette's often-covered "Darcy Farrow," which as faux-Western tunes go is pretty much the gold standard. The closer, the brooding "Houlihans at the Holiday Inn," concerns a cowboy singer whom time has transformed into an act at the mentioned establishment. The song takes its power from the jarring disjunction between the two lives the character has lived. All three of Wall's albums, released beginning in 2017 and each improving on the one before it, sit on my shelves. Cowboy folk music is nothing new, of course, though I might clarify here that Wall takes a different tact from its most famous living practitioner, Alberta's Ian Tyson. While I could not admire Tyson more than I do, Wall has set out on his own trail. In handling the material, he emerges as less a Tyson acolyte than one of Tyson's older sources. I hope he keeps doing what he's doing.

|

Rambles.NET music review by Jerome Clark 3 October 2020 Agree? Disagree? Send us your opinions!

|