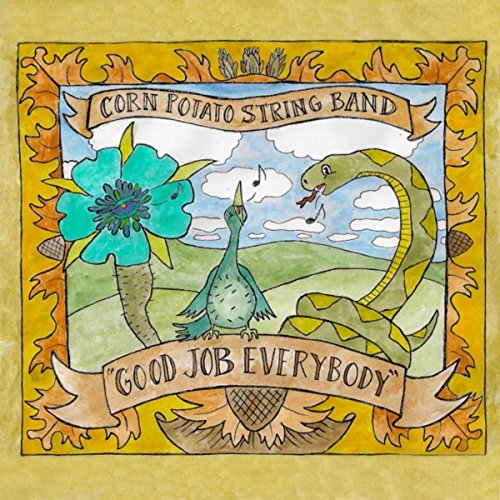

| Corn Potato String Band, "Good Job Everybody" (independent, 2017) The Down Hill Strugglers, Lone Prairie & Other Old Time Songs (Jalopy, 2017) Though having no musical gifts myself, I've been enamored of traditional music since my youth -- which was, ahem, a few years ago -- but when I started out with it, I could not have imagined how much of it I would hear over the ensuing years, or how my head would get overloaded with arcane information about America's vernacular sounds. There comes a time, in short, when you're hearing little that's truly new, unless an artist is modernizing something nearly beyond recognition. Where old music done the old way is concerned, what the seasoned listener hopes for is an approach that, for all its familiarity, communicates freshness and joy. Freshness and joy are here to be savored in these new discs by two young oldtime string bands. In common with the music that has sustained me in good times and bad, the Corn Potato String Band and the Down Hill Strugglers light a warm glow in my heart every time I hear them.

The band consists of Aaron Jonah Lewis, Ben Belcher and Lindsay McCaw, each proficient on two or more stringed instruments. The liner notes to "Good Job Everybody" (recorded, oddly, in Scotland) don't tell us who's singing what, though it's obvious that McCaw, representing the female contingent, is doing a good part of it. You can tell they're having a whole lot of fun without, however, letting goofing get in the way of putting their songs and tunes across. Even the cornball songs, for which they have a manifest affection, are delivered with such a nuanced balance of earnestness and absurdity that the way you come down when you hear them may vary from exposure to exposure. That's pretty neat, and you don't do that to your listeners if you aren't in full command of everything you're up to. Though arranged as if it were, "I Let the Stars Get in My Eyes" is not a venerable Appalachian number but a 1953 country hit by Goldie Hill, an answer to the insanely popular "Don't Let the Stars Get in Your Eyes" (covered by Ray Price and Perry Como among others) the year before. There's nothing amid the 13 cuts not to enjoy, but let me give "Flying Saucers" a shout-out. It's a borderline-nutty gospel warning originally cut by the Buchanan Brothers in the fall of 1947, inspired by the then-novel sightings that had erupted that summer amid massive press coverage and widespread speculation. Even more eccentric is the bawdy "Sal's Got a Meatskin," sung as if it were an unusually sad love song (or for that matter a lament for a lover the singer has lately murdered) while its actual subject matter is horniness. "Good Job Everybody" -- a wonderful title; those quotation marks are inspired, not to mention hilarious -- weds obscure mid-century country and older Southern folk music in a thoroughly charming union. Good job, everybody.

More popular than ever among young musicians, old-time shows up these days in all kinds of forms, as strictly traditional exercise or as vehicle for modern exploration (as in Old Crow Medicine Show's recent neo-oldtimey reimagining of Dylan's Blonde on Blonde). As is always the case, what matters is whether the approach, whatever it is, works on the terms it's set out on. The Strugglers are hardcore traditionalists in the NLCR vein, meaning that they draw their repertoire from the classic hillbilly-folk 78s of the 1920s and occasionally from songs collected in the field in the first half of the last century. Since the 1960s a great quantity of this source material has been reissued. (I have more of it my CD collection than I can keep track of.) If a 21st-century band seeks to resurrect the music in the antique style, it had better know what it's doing, or stale rehash is the inevitable consequence. As with the Dust Busters, the Down Hill Strugglers never have to wrestle with that problem. In some almost mystical sense they inhabit the music, as if they were born with it imbedded in their genes. Yet they claim no actual Appalachian connections to speak of. Still, everything they do feels organic, authentic, and true. Even their visitation of the well-worn title tune, as with standards "St. James Blues" (aka "St. James Infirmary") and "Casey Jones," feels startlingly revelatory. My only complaint is the 13 cuts as opposed to the 20 on Old Man Below. Once the tunes start (with a full-blooded arrangement of the fiddle piece "Last Shot Got Him"), you don't want them to stop. When they do, you'll be tempted to play them all over again. And speaking of temptation, I have to resist the same to pronounce the Strugglers the finest folk band in any genre currently performing in America. Then again, maybe I won't.

|

Rambles.NET music review by Jerome Clark 1 July 2017 Agree? Disagree? Send us your opinions!  Click on a cover image to make a selection.

|